Seeing the Ends of the Earth Alters Your Idea of the Planet, Author/Explorer says

Neil Shubin dreamed of studying rocks, not ice. But then a surprise invitation to East Greenland landed as he finished his doctorate at Harvard. Despite a lack of camping skills, Shubin joined three researchers trudging across the Arctic in search of early dinosaurs.

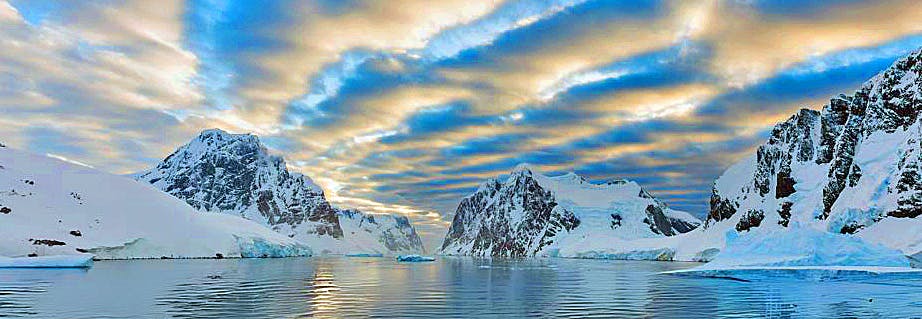

The rookie paleontologist’s trek into a land of wild, beautiful and unpredictable extremes captivated him, forever changing the course of his work and his view of the world.

“Little did I know that would set up almost four decades worth of work up there leading my own expeditions,” Shubin tells me in an interview. “And really what happened is what happens to many people who work in these regions and visit them. They really get in your blood. They change the way you see our planet and how it works.”

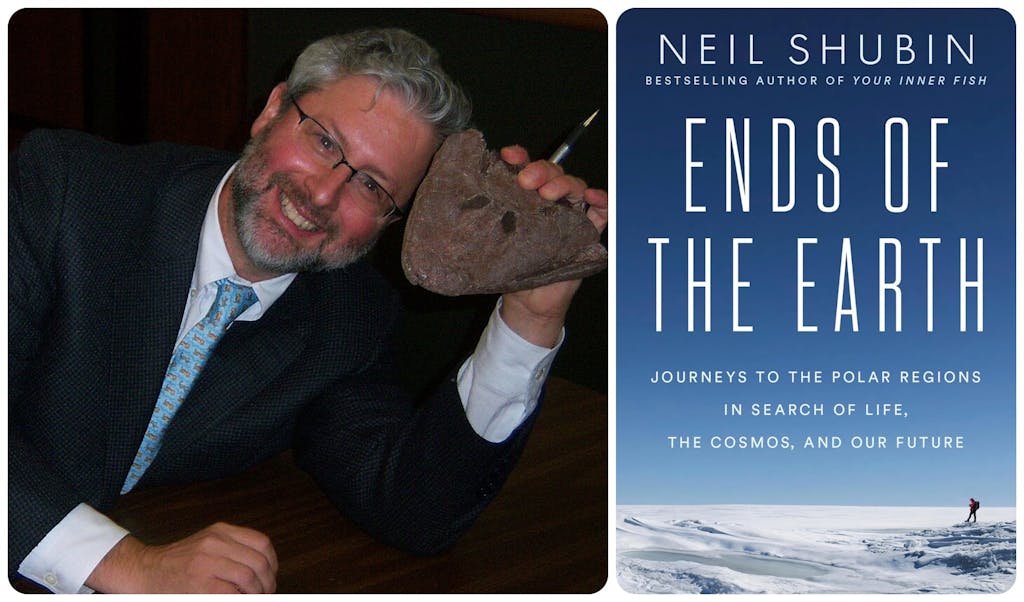

Shubin’s recently published “Ends of the Earth: Journeys to the Polar Regions in Search of Life, The Cosmos and our Future” chronicles his adventures throughout the Arctic and Antarctica. He weaves together polar history, science, climate, tech and first-person travelogue.

Creating an infectious curiosity

His lens is one of boundless curiosity and it’s infectious. “Ends of the Earth” is an eye-opening resource for travelers venturing to these fragile corners of the world, as well as anyone interested in the polar regions’ profound impact on humankind’s past and future. (Shubin shared his own polar reading list, and you’ll find it below.)

Shubin offers this advice to anyone following in his footsteps: “Understand you’re going to one of the most special places on planet Earth. Whether it’s Antarctica or the Arctic, you’re going to a place very few human beings have set foot on before. The more you study the natural history and the science of these areas, the more you really understand how we’re tied to these places.”

When he’s not leading polar expeditions, the 64-year-old author holds a day job as a professor at the University of Chicago. Shubin, an evolutionary biologist, also hosted the Emmy Award- winning PBS miniseries “Your Inner Fish,” based on his bestselling 2009 book of the same name. It’s the story of how Shubin’s research team discovered Tiktaalik, the 375-million year-old fossilized remains of the first fish to walk on land, on Ellesmere Island in the Canadian Arctic.

In our conversation, Shubin talks about the slow, painstaking life of scientific research followed by a groundbreaking moment of “complete eureka and incredible beauty” on a glacial river.

“We’re working these rocks, pulling out bones, and one of my colleagues asked me, ‘Hey, Neil, what’s this?’ And I looked down, and I saw what we were looking for, what we had spent six years looking for. And I saw the fish, which is one of our distant ancestors, a fish that has fins with arm bones inside.

“Imagine this: I’m standing at this landscape where you can see musk ox in the distance. You see glaciers and ice. We’re working on the rocks, of course, but inside the rocks is a tropical world inside the world, so you have this juxtaposition between present and past. We’re pulling these fish out of these rocks in the Arctic, but we’re in an Arctic landscape today.”

The ‘stuff of goosebumps’

Shubin describes polar science as a window into the “profound connections” between oceans, climate and all living beings.

He recalls an earlier 1989 expedition doing fieldwork in coastal Greenland when the weather changed for the worse. Racing back to camp, he and a colleague stumbled on what turned out to be the Dinosaur Dance Floor, a sandstone ledge about the size of two tennis courts covered with dinosaur tracks. “When I look down, I see in the rock a print that looked like a giant bird, three-toed with a claw on the end. And that led to another one and another one and another one.”

“The stuff of goosebumps,” he says.

Glacial pace? Not at the poles

Shubin’s new book brings to life exotic, resilient creatures that have adapted to survive the coldest places on the planet. His favorite? The Arctic woolly bear caterpillar. This tiny ball of fur hibernates and freezes like an ice cube to live for seven or eight years. It also has developed a trick to survive freezing: The woolly bear makes its own antifreeze, a natural protein that prevents ice crystals from destroying its cells. “It has, in a nutshell, many of the inventions that are necessary for surviving in these extreme environments,” he says. “It’s just an awe-inspiring little caterpillar.”

Shubin says his journeys have upended many preconceived ideas about the polar world, such as the notion of a “glacial pace.” Things actually can move quite fast at the ends of the Earth. Everyone thinks they know ice from their own experiences, but Shubin says it’s entirely different at the poles, a complicated, crazy mystery in its forms, depth and movement. “We really don’t understand how ice behaves, especially when it’s the size of the state of Florida,” he says.

‘We really don’t understand how ice behaves, especially when it’s the size of the state of Florida.’

Neil Shubin, author and explorer of polar regions

“One of the things that I found in doing my own research and talking to other scientists was the fact that if you drill two, two and a half miles under the ice in Antarctica, you find freshwater lakes, some of them the size of one of the Great Lakes in North America. These lakes contain living creatures that have been separated from the surface for thousands, if not millions of years. That shows the kinds of surprises and hidden wonders that lie underneath the ice, how we still have so much to discover.”

In “Ends of the Earth,” Shubin also recounts a 2018 expedition to McMurdo Station, the largest scientific outpost on the Antarctica continent, arriving aboard an Air Force LC-130 propeller plane. Shubin is suited up in Big Red, a giant blanket of a coat designed for extreme weather, which he describes as a “warm home away from home in the field.”

After an 11-hour flight from New Zealand, Shubin emerges in a cold, dry and searingly bright world. “Slipping on the hard-packed ice, I soon realize I would need to learn new ways of walking, living and working in this environment,” he writes.

Mactown, as the locals call the station, sits on a volcano and is one of three bases run by the U.S. Antarctica Program. It houses more than 1000 people in summer and dwindles to 300 in winter. “It feels like a waystation similar to the fictional Mos Eisley spaceport in “Star Wars” or Rick’s Cafe from “Casablanca,” Shubin writes. “The entire population is temporary.”

Shubin says he’s always chilled to the bone and ravenously hungry for the first few days of an expedition, which usually lasts four to six weeks in the Arctic and eight weeks in Antarctica.

“After about a week, I’m fully adapted. It’s those first four days, which are pretty brutal. You learn to get dressed in the tent. You learn little techniques and tricks to make yourself more comfortable. And those are kind of key when you’re in a tent at 0 degrees or minus 10. The hardest thing to get used to there is the daylight 24 hours a day.”

Shubin, who enjoys making pizza at home in Chicago, says he puts great care into assembling flavorful meals and desserts for his expedition teams. “I noticed that people like extra salty, extra spicy, extra sweet,” he says. His own favorites are Mexican, Indian and Thai foods, tons of chocolate including Toblerone bars and all kinds of licorice.

”Food is more than sustenance because you’re burning a lot of calories in these places,” he says. “Because we’re walking 10 to 20 miles a day, climbing, doing a lot of physical exertion. But also food is mental sustenance as well. Having good meals and having great snacks and having excellent food is a way to keep morale very high.”

Books to read ahead of a trip

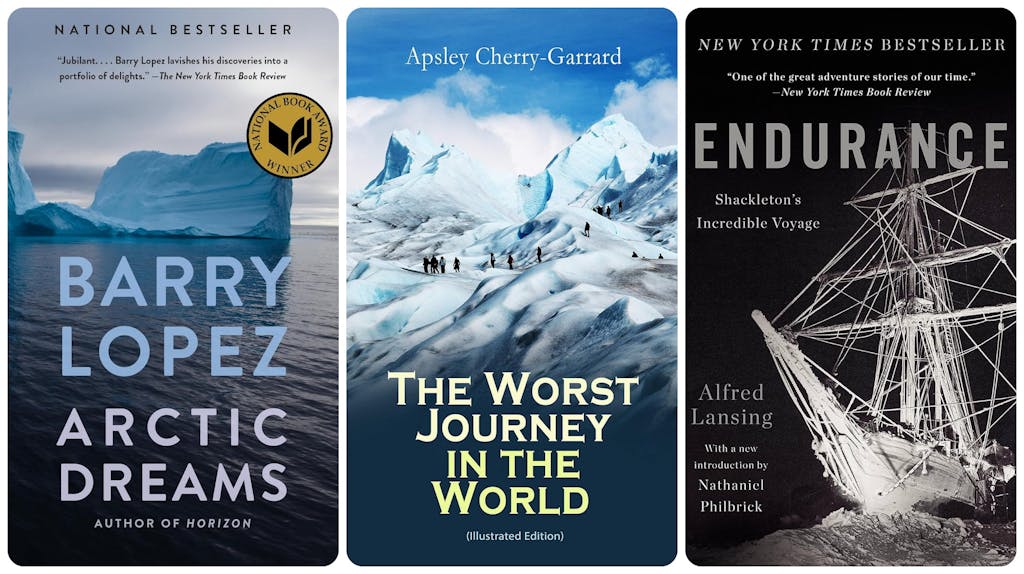

Before setting out on your own polar adventure, Shubin recommends reading these three books:

“Arctic Dreams, ” by Barry Lopez. Musk oxen, polar bears and narwhal roam this bestselling natural history and travelogue, which won the National Book Award. “I read it on my first expedition, and I’ve read it a couple times since,” Shubin says. “That one is one of my favorites.”

“The Worst Journey in the World,” by Apsley Cherry-Garrard. The author, a member of Robert Falcon Scott’s 1910-12 South Pole expedition, published his account in 1922. “He wrote eloquently about one of the most challenging expeditions out there,” Shubin says. “It’s bone-chilling. It’s incredible. (Scott) did all this exploration in the search of penguin eggs.”

“Endurance: Shackleton’s Incredible Voyage,” by Alfred Lansing. Polar explorer Ernest Shackleton set sail for Antarctica in 1914 and planned to cross the continent on foot. “Endurance” details Shackleton’s ill-fated trip.