The Renaissance of Alaska’s Totem Poles: Where to See Them, Why They Matter

“Here — why don’t you give it a try?”

The Haida artist in a carving shed in a remote town in Southeast Alaska hands me a small adzing tool used to scallop a distinctive rippled pattern on the 30-foot Western red-cedar log he’s fashioning into a totem pole. I grasp the adz firmly in both hands and attempt a cut.

Yikes. Misshapen, ragged, uneven and rough.

I try again. Same amateurish result. I hand the tool back to the carver, Harley Holter, and he greets the hand-back with a friendly, ironic grin. “Not as easy as it looks, yes?”

Indeed.

It takes immense skill, experience and dedication to produce one the world’s most familiar and distinctive art forms, the totem poles of the North Pacific coast. Almost instantly recognized from Tokyo to Topeka, totems stand tall in the public imagination — and in real life.

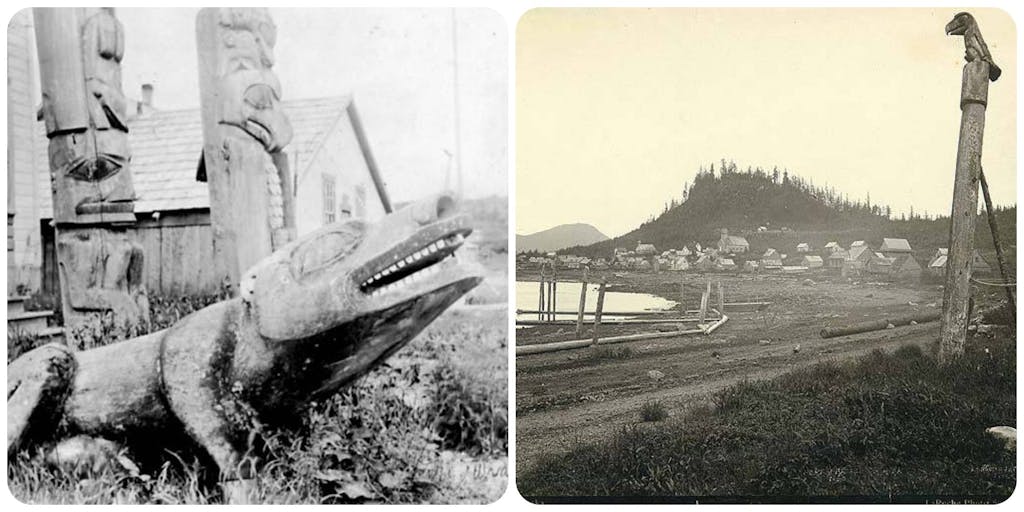

Museums worldwide display historic totems to illustrate how avidly these icons of indigenous life were collected in the 19th and early 20th centuries, and they induce images of misty forests, sparkling fjords, charismatic bears, eagles and whales, and coastal enclaves along one of the world’s most complicated coastlines.

Those images are accurate, to a point. But the work in Holter’s carving shed — and many others from Seattle to Anchorage — illustrates something just as important as the historic prominence of totems: This is an art that’s not only alive and well but is also undergoing a huge cultural renaissance.

Alaska’s Native peoples of the Southeast coast have been commissioning new poles by the dozens in the 21st century, for reasons that resemble traditional motives but with modern embellishments. Look for modern poles adjoining historic ones in public spaces and along the waterfront in Ketchikan, Wrangell, Sitka, Juneau, Haines, Cordova and Anchorage, among other ports of call.

To preserve the past and ensure the future

Two centuries ago, totems lined the waterfronts of indigenous coastal villages to declare who lived there, not just what nation (Tlingit, for instance) but which division and clan.

Take the Kiks.adi of Wrangell. The clan symbol is a frog, so totems would likely incorporate one of these creatures. Wrangell was in the Raven moiety, that is, the broad classification that divides Tlingit society into two, so a raven might appear as well. Salmon, whales, otters, bears, sea lions and notable clan leaders might also climb the pole to its top, where Mr. Frog would pose in hegemony over all.

The origins of totem carving are lost in the mists of North Pacific time and may date back hundreds or thousands of years. European contact brought carvers better tools and more vivid paints, and the art blossomed in the 19th century.

Explorers and collectors recognized the marketability of totems. Hundreds were taken by various means from the North Pacific Coast to museums around the world where they became the anchors of displays about Pacific Northwest culture.

Today, Juneau’s new 10-pole Trail of Totems makes a broader modern declaration: We, the Tlingit, Haida and Tsimshian peoples of Southeast Alaska, are not only still here, but we also are thriving and prospering in a world where handmade arts fade farther into a past we believe has valuable lessons for the Instagram era.

Juneau’s Sealaska Heritage Institute, funded by the Mellon Foundation Institute, hired 10 famous carvers to create these poles while also including funds for apprentice carvers for each one.

“We discovered that there aren’t a lot of master artist Northwest Coast totem pole carvers,” says Rosita Worl, president of the institute.

“SHI’s Native Artist Committee considers a person a master artist totem pole carver if he/she has carved at least five totem poles. With the limited number of master totem pole carvers, the mentor-apprentice arrangement became a vital component of the project.”

In other words, this craft is worth saving, and SHI is setting about doing so. The first 10 poles were raised in 2023; eventually, the Juneau display will comprise 30 poles, perhaps the largest such collection in the world.

Messaging and superlatives are nothing new for totems.

Consider what may have once been the most famous such pole in the Alaska Panhandle, the Seward Shame pole of Saxman Village, a Tlingit enclave just outside Ketchikan.

U.S. Secretary of State William Seward stopped here in 1869 on an Alaska tour to see what he bought in 1867 from Russia. (Photo by Gary Bembridge at top of page is a Saxman Village totem, 2018.)

Saxman’s Chief Ebbits showered the secretary with gifts and mementos, but Seward never reciprocated after he returned to Washington, D.C. Saxman carvers erected a pole with Seward’s likeness at the top and painted it red in shame.

A new version was carved and raised in 2017 by famed Tlingit artist Stephen Jackson, on the Alaska purchase sesquicentennial, to rededicate Alaska Native objections to the process.

The height of totem culture

Totems generally top out around 40 feet. The well-known Kwakwaka’wakw pole in Alert Bay, at the north end of Vancouver Island, which holds title as world’s tallest, although it’s a controversial title, because it is made of two pieces, not one, and must be supported by guy wires. Most totems are stand-alone timbers of natural strength. A 140-foot single span pole in Kalama, Wash., was carved by non-Native artists, so totem aficionados discredit that one.

The new totems that are distinctly visible in almost every port along the Gulf of Alaska will enjoy the lifespan intended for totems generations ago: Carved and raised by indigenous people to honor their clans and communities, over time they slowly surrender to the North Pacific’s greatest power — nature — and eventually return to the ground whence they came.

At that point, we hope, new totems by new carvers will rise to represent clans and communities new and old.