Meet the “Darwin of the East”: The Extraordinary Life of Alfred Russel Wallace

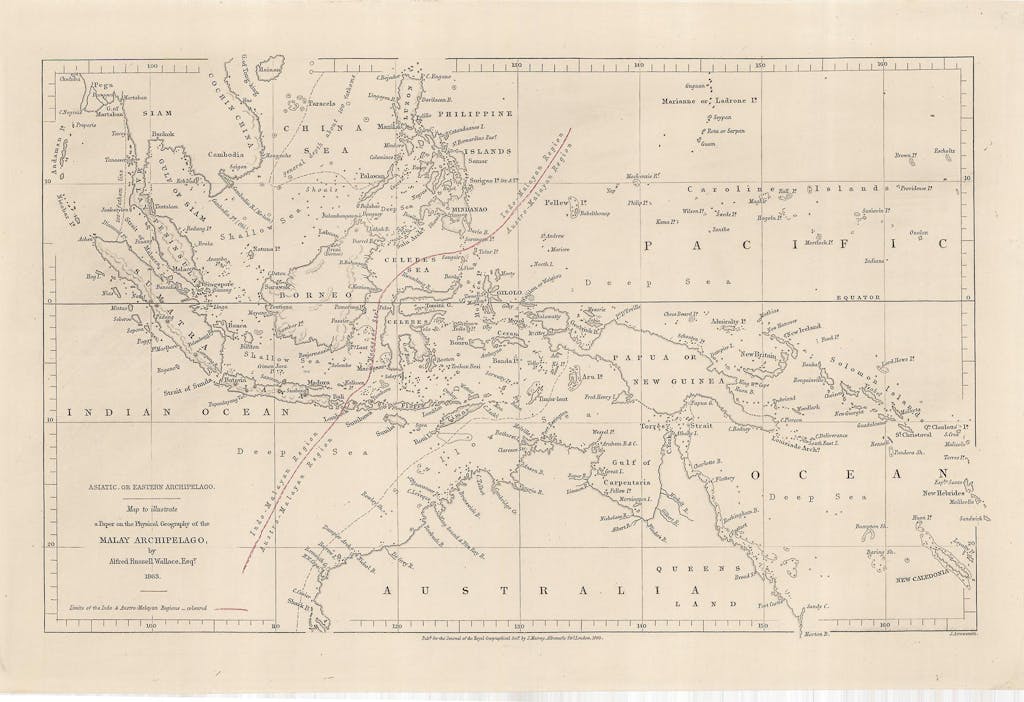

The strait between Indonesia’s lush, mountainous islands of Bali and Lombok is short; only 25 miles across. But the two islands are separated not just by sea. Astonishingly, in terms of biodiversity, they’re worlds apart. In fact, during this short sea passage, you’re crossing the invisible Wallace Line, named after 19th century British explorer Alfred Russel Wallace.

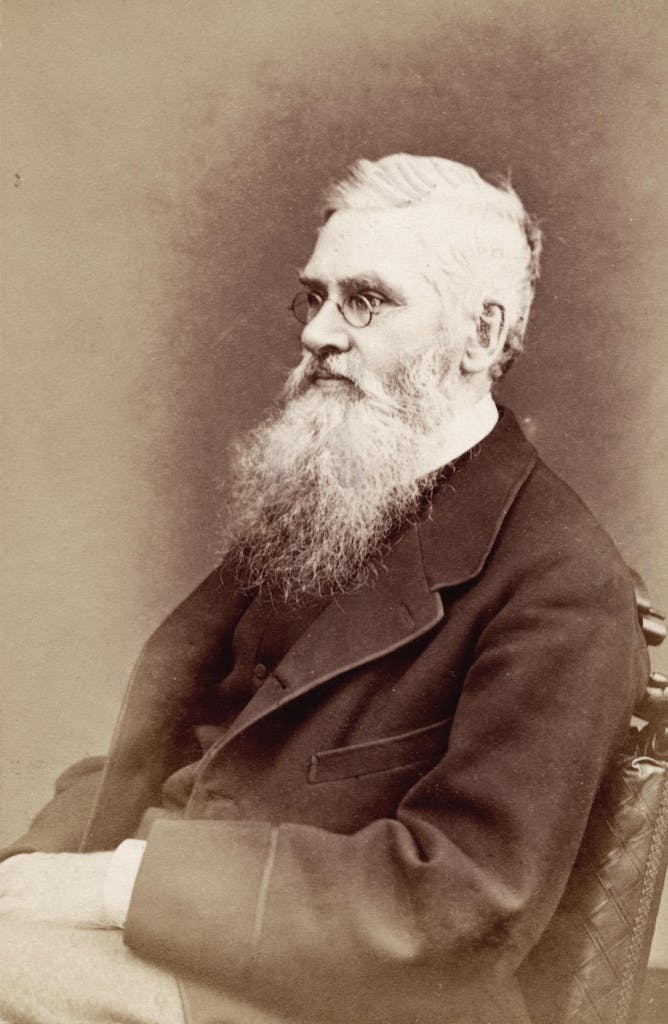

You’d be forgiven for wondering, “Who?”, and “What?”. Who indeed? Wallace was a 19th century naturalist, geographer, explorer, evolutionary biologist and social commentator. He’s been dubbed the David Attenborough of his time.

Remarkably, Wallace came up with a theory of evolution by natural selection at around the same time as Charles Darwin, completely independently of his contemporary and on the opposite side of the world. Yet it’s Darwin who to this day is credited with developing the theory. In Asia, Wallace remains a household name. In the West, most have barely heard of him.

Was Wallace robbed of the glory he deserved? While he remains a household name in southeast Asia, his achievements are largely overlooked in the west. This is the story of an extraordinary man, and how his legacy may touch your own exploration, from the rainforests of Asia to the great scientific institutions of London, not to mention the Galapagos Islands and beyond.

To understand the story of these two great thinkers, and to consider whether this was, indeed, a scandal of its time, means taking a voyage of discovery, metaphorical or otherwise, from Singapore, Bali, Lombok and Borneo to the Galapagos and finally, London.

This, then, is the tale of Wallace – and how his legacy may touch your own exploration, from the steamy rainforests of Asia and the great scientific institutions of Britain.

Born in Wales in 1823 and leaving school at 14, Wallace was a fearless explorer, self-taught and self-funded. Despite much of a formal education, he became one of the most important scientists of the era, publishing more than 1,000 papers on everything from anthropology to ethnology and epidemiology. Yet Wallace was essentially a Victorian-era backpacker; an outsider in scientific circles of the day, which were mainly populated by a wealthy elite, of which Darwin was a well-connected member.

Belief about the origin of species in the early 19th century centered around creationism; the thought that each animal, bird and insect had been created by a higher power, bestowed with characteristics appropriate to the environment in which it lived.

Wallace was constantly asking himself: where do species actually come from? Why, for example, were birds from the Amazon completely different from birds in Indonesia, where the climate is similar? His first expedition, in 1848, took him to the rainforests of Brazil, in a quest to piece together this puzzle. He collected thousands of specimens of animal, insect and bird from the middle Amazon and Rio Negro but on the journey home in 1852, his ship caught fire in the Atlantic and sank. Wallace and his fellow passengers were rescued after 10 days in a leaking lifeboat, but all his specimens apart from a couple of notebooks and one parrot were lost.

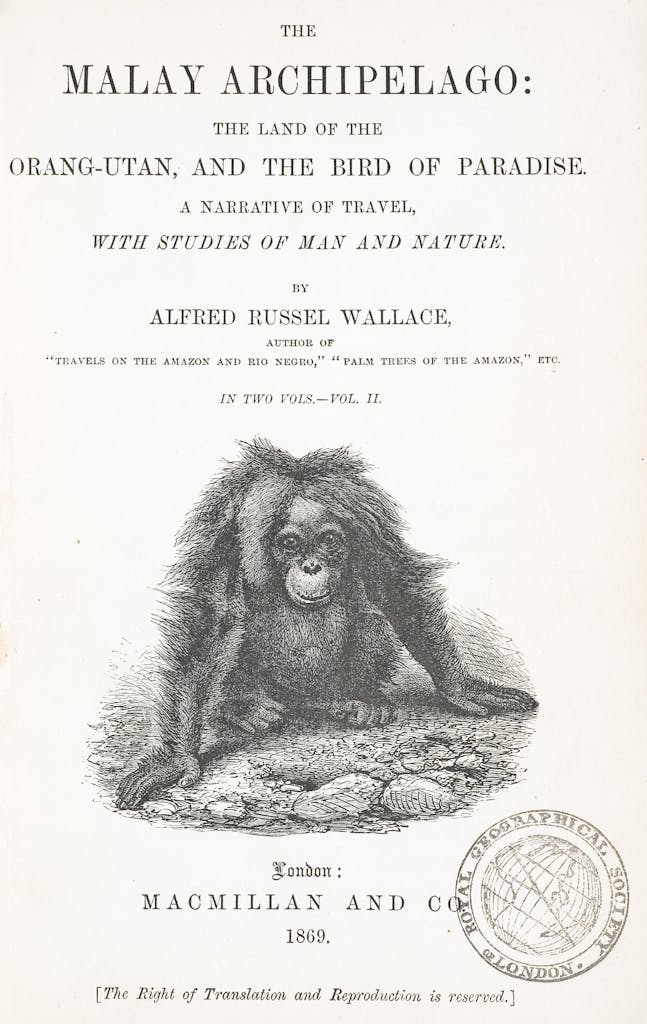

Undeterred, Wallace set off for Asia in 1854 on a journey around the Malay Archipelago – modern day Indonesia and the Philippines – that would last eight years and cover 14,000 miles. During this period, he would collect 110,000 insects, 7,500 shells, 8,050 bird skins, and 410 mammal and reptile specimens, including more than 5,000 species new to science.

Wallace was an avid collector of butterflies, particularly the brightly coloured birdwing species. He began to observe that these creatures varied in appearance depending on which island of the archipelago they came from. The mystery of these variations and their distribution deepened as he explored Asia. In Borneo, he came across monkeys and orangutans. Singapore still had tigers in those days. But in New Guinea, not that much further east, he found tree kangaroos, a type of marsupial.

Wallace began to plot on maps the islands on which the animals had pouches, and the islands on which they did not. He concluded that the animals to the east of the archipelago were related to creatures from Australia, whereas the creatures on the west – monkeys, tigers and rhino – resembled species found in Asia.

Most tellingly, on Lombok, the species were completely different from those on Bali, a mere 25 miles across the water. It was as though a clear line split the archipelago down the middle, extending north between Borneo and Sulawesi and along the eastern edge of the Philippines archipelago.

In fact, the line Wallace had imagined, which would later be named after him, followed the contours of the Asian and Australian continental shelves, which was not known at the time. During the last ice age, when sea levels were up to 390 feet lower, the islands to the east of the line were connected to Australia and those to the west joined to Asia. Animals could cross from Australia to what’s now Indonesia – but they couldn’t cross the deep ocean trench between the continents. These animals, separated by physical geography, Wallace realized, had adapted to their surroundings over the millennia and changed.

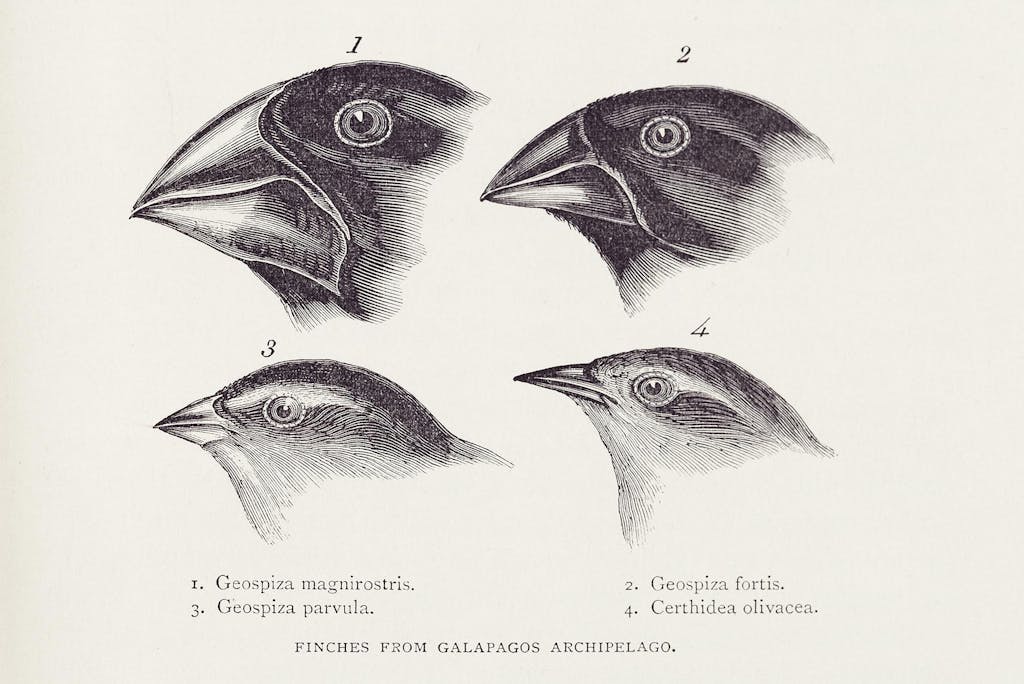

Let’s now step back 20 years or so. In 1835, the young Charles Darwin, a wealthy and passionate amateur naturalist, reached the Galapagos Islands on the brig, HMS Beagle, during a five-year expedition. Darwin only spent five weeks in the archipelago, but the theories he developed were ground-breaking. He observed that finches and mockingbirds of the Galapagos had distinctively different characteristics, depending on which island they came from.

Darwin began to consider the radical idea that rather than being fashioned by a higher power, species may have the ability to change, adapting to their situation in order to survive. At the time, though, this kind of thinking was still regarded as heresy. Rather than publish, Darwin kept his theories to himself.

Fast forward again to Indonesia, 1858. Racked with fever in his hut on the steamy, volcanic island of Ternate, Wallace, still puzzling over evolution, had an epiphany. The theory that human populations were kept in check by famine, disease and war was already accepted. But what about animals? How had the animals either side of his ‘line’ developed to have such different characteristics from their ancestors? “Why do some die and some live?” he later wrote. “And the answer was clearly, that on the whole, the best fitted live.” Wallace had realized, in other words, that natural selection was the mechanism by which species evolved. The strongest would survive, passing on their characteristics to later generations.

Excitedly, Wallace shared his ideas in a letter to Darwin, whom he admired and with whom he had corresponded in the past. Back in England, Darwin was still dithering over this own theory. Startled by the similarity to Wallace’s very lucid thinking, Darwin consulted his colleagues, the geologist Charles Lyell and John Dalton Hooker, a botanist.

Rather than help Wallace publish, therefore scooping Darwin and depriving him of glory, Lyell and Hooker decided to present Darwin’s hastily scribbled writings, along with Wallace’s paper, to London’s Linnean Society, the world’s oldest biological society. The resulting set of papers, with Darwin’s name first, was published as a single article.

Darwin abandoned the massive tome he was writing on evolution and quickly rushed out a shorter book. In 1859, while Wallace was still in Asia, Darwin published On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, earning himself a place in history.

Despite Wallace arguably having been robbed of the fame he deserved, the two men became lifelong friends and Wallace, encouraged by Darwin, won many prestigious awards for science. Wallace’s The Malay Archipelago was published in 1862 and is still regarded as one of the greatest pieces of travel and scientific writing of the time. But the theory of natural selection is to this day primarily credited to Charles Darwin.

Scratch the surface on your travels through the Malay Archipelago and the legacy of Wallace remains, not just in his famous line but immortalized in the Latin names of more than 200 species of butterfly, amphibian and bird of paradise. The bio-geographical region of Indonesia, which he explored in such depth, is still called Wallacea.

In Singapore, there’s an informative Wallace Education Centre and nature trail at Dairy Farm Nature Park in the Bukit Timah Nature Reserve, a short hop from the port.

Should your travels bring you to London, there’s further chance to pick up the Wallace trail. Some of Wallace’s insect collections are displayed in the Natural History Museum, along with his portrait. The Linnean Society still exists, its headquarters in Burlington House on Piccadilly.

Plus, you can explore the Collections of our Corporate Business Partner, the Royal Geographical Society (with IBG), who hold maps and images which illustrate this article and who provide bespoke, itinerary-focused scientific and historical expedition information, enriching the journeys of Silversea guests with knowledge specifically tailored from their two-million Collections items, which document over 500 years of global travel.

Wallace died in 1913 and was buried in a public cemetery in Dorset – a far cry from Darwin’s high-profile funeral in London’s Westminster Abbey. Still, in 1915, a plaque was added next to Darwin’s memorial in the Abbey. If you’re visiting, take a moment to pay your respects to one of the great unsung heroes of 19th century science and exploration.

This article has been produced in collaboration with Silversea’s Corporate Business Partner, the Royal Geographical Society (with IBG), which enriches guests’ expeditions with over 500 years of geographical travel and discovery. Find out more here.