On South Korea’s Jeju Island, Diving ‘Sea Women’ Create a Kind of Marine Magic

Jeju Island, about 60 miles off the South Korean peninsula, is tiny as islands go, and just a bit smaller than Maui, with which it shares some similarities: Both are tropical, volcanic islands, known for beauty, beaches and waterfalls.

But only one is home to communities of haenyeo, or “sea women,” the acclaimed divers of South Korea who harvest abalone, sea urchins, seaweed and more while submerged as long as three minutes on each dive. They do not rely on artificial breathing apparatus but on the strength of their lungs and their years of experience. Many are well beyond standard retirement age and still diving, sometimes into their 80s and even 90s

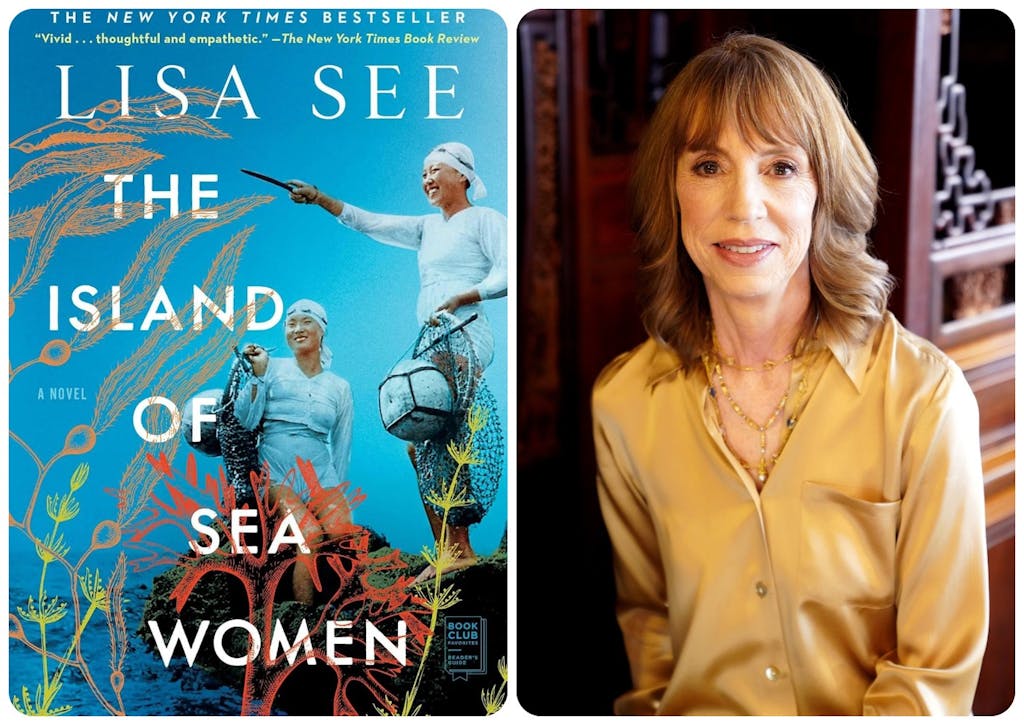

You can learn more about these remarkable women, thanks to best-selling author Lisa See’s “The Island of Sea Women,” a work of historical fiction that intertwines friendship, history, conflict and, most of all, a culture replicated nowhere else in the world.

See sat down with me to talk about the unexpected way she discovered the story and the resulting magic she found in Jeju. (This interview has been edited for length and clarity.)

Catharine Hamm: What attracted you to this story?

Lisa See: I was in a doctor’s office flipping through magazines, waiting to be called in, and there was a 2-by-2 inch photo with about the same amount of text about these divers. And I ripped it out of the magazine and brought it home. Yes, I’m the person who does that.

That day when I came home, I started looking stuff up about them because I loved that they were diving at such advanced ages.

But I was also completely obsessed with the fact that they had this ability to withstand cold water. They used to dive in…in winter without wetsuits. One of the things I found that very first day was an old article in Scientific American that was the result of studies that had been done about human beings having an ability to withstand cold water.

One of those groups were the haenyeo and that they had the greatest ability of any human group on Earth to withstand cold water. That fascinated me.

CH: How long did it take to create this from the time you said, ‘OK, the clock starts now’?

LS: Two years.

At first, I was slowly gathering material, but I wasn’t in a rush to write this. Then in 2016, UNESCO gave the haenyeo the designation of an “Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.” Part of the reason they were doing that was that they anticipated that this culture was going to disappear from the Earth within 15 years.

By that time, I knew that a lot of these divers were in their 70s, 80s and 90s. If you want to interview someone that age, you take a big risk waiting five, 10, 15 years to go and interview them. I felt like I had to do this now. And that’s what I did.

CH: How much time did you spend on Jeju?

LS: About two weeks.

CH: Wow, that was a fast trip.

LS: I do so much research ahead of time so that when I’m there, fact gathering is very targeted. If you read an article about the haenyeo, there are certain things that are going to be covered no matter who’s writing it. I’d already read the answers to those questions.

One of the nicest compliments I would get from the divers was, “You asked me things no one’s ever asked before.”

I think about these women a lot, and it’s very sad that it is coming to an end. I mean, they’re never going to be replaced. There’ll be some young women who do it, but it really is going to disappear. I have been inspired by their courage, their persistence, their endurance and their great sense of humor.

And to be able to just look to those women and think, ‘Well, they’ve been through so much and they’re still working and they’re working at an old age.’ One woman I interviewed was 93 years old and still diving, still earning a living diving.

CH: Was there anything that startled you or was very different from what you thought it would be?

LS: There are three very different things.

One was the sound the women make when they come up, and they let out the air and take a new breath.. Every woman makes a different sound. It’s called a sumbisori.

One day I went to a jetty at the end of the day. Men had gathered there to lift the heavy nets out of the water for the. I asked them how they could tell which diver was their wife or mother. They would answer, “I hear her sumbisori when she comes up. That’s her right there.”

That’s one thing to read about the sumbisori, but another when you hear it. Beautiful. Haunting.

Another had to do with the natural aspects of the island. Yes, there’s the shore, and you could say it doesn’t matter where in the world you are, if you’re on a beach, it’s a beach. Jeju is made from one huge volcano, but it also has hundreds of cones, baby volcanoes that are part of the bigger one.

And then there was the information about the April 3, 1948, incident, the day Jeju Uprising, often called the 4.3 Incident began, and then to see how it permeated the culture all the way to today.

Editor’s note: The unrest, spawned in part by the proposed division of the Korean peninsula, began just before South Korea’s first general election. Government security forces struggled until 1949 to quell the fighting, although it continued into the 1950s. The number of people who died in the turmoil is only an estimate, ranging from 12,000 to 30,00, and some say it is at least double that latter figure.

LS: Here was this terrible thing that happened, which was then followed by 50 years of government censorship under pain of torture, imprisonment, death. It was serious. But today island is recognized internationally as the “Island of Peace.”

CH: If you were going to be in Jeju for one day, what would you do?

LS: I would go to the haenyeo museum, which is in a little town called Hadori. And along the way, you’ll be going along the coastline, so you’ll hear the sumbisori. You’ll probably see women in the sea. And the museum is terrific.

Another place I found really moving is the April 4 (the 4.3) memorial. Not everybody wants to go to a memorial when they’re on vacation, but this one is especially moving. It has a sweeping marble wall with the names of everybody who died in. It’s in a beautiful spot that overlooks everything. It reminded me in many ways of the Vietnam Memorial in Washington, D.C.

This is getting to be a lot for one day, but take a walk one of the Olle trails. All of the villages all the way around the island are linked by these pathways, and they go through really beautiful areas.

CH: What do we still need to tell travelers who visit Jeju?

LS: Go get a meal. I would recommend two things. One could be lunch and one could be dinner. There are restaurants that are run by the haenyeo themselves, but there are also places where they come out of the water and they just sit on a bucket and you come up and they’ll open oysters for you, or they will slice raw octopus and you’re just eating it right out of the water. If you love abalone, make that part of your meal, whether you’re getting it from a woman sitting on a bucket or in one of the seafood restaurants.

The other thing that Jeju is known for is black pig. It is unique. If you eat pork, you’ve got to try this. It is delicious, and you’re never going to have it anywhere else. It’s very juicy.

Another food you should try is this special Jeju orange that grows only on Jeju island. You can buy those. You can pick up candies, you can pick up marmalade. You can buy the fresh oranges, but they are also used to make candies, pastries, and marmalade. Anything you can think of that could be done with an orange—and more!—is done on Jeju.

One other thing that is very high up: Go to the big markets or the farmers’ market. They are beautiful and colorful, and you get a sense of how people live.

CH: Did you try sea urchin?

LS: I love sea urchin. I’ve already mentioned the women who sell just-caught seafood right on the street. These items couldn’t be fresher. If you’re anxious about eating street food, this is literally from the ocean straight to you.