Enduring Eye: A Look Back at Ernest Shackleton’s Epic ‘Endurance’ Expedition

In Silversea’s “On the Map” series, we highlight our special partnership with the Royal Geographical Society (with The Institute of British Geographers) to bring you exclusive content collated from centuries of scientific exploration. The Society’s Collections comprise of over two million documents, maps, photographs, paintings, periodicals, artifacts and books, and span 500 years of geography, travel and exploration.

On the 21st of November, 1915, the three-masted barquentine Endurance sank beneath the ice in the Weddell Sea off Antarctica during the Ernest Shackleton-led Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition that began a little over a year earlier. Exactly 100 years after that fateful date, the Royal Geographical Society with the Institute of British Geographers launched a special exhibition at the institution’s South Kensington headquarters in London. The curated exhibition featured artefacts from the expedition as well as an impressive collection of photographs that bore witness to the trials and tribulations faced by Shackleton and his crew.

As part of the Society’s exclusive partnership with Silversea, the centenary of Shackleton’s expedition was also commemorated aboard Silver Explorer, where guests had the opportunity to retrace Shackleton’s steps in select Antarctic voyages.

At the heart of this special celebration stood a specially curated gallery of images by the Endurance’s official photographer, Frank Hurley, who was selected by Shackleton to document the expedition in film and in stills. The remarkable images that were taken during the Endurance expedition by the Australian photographer are some of the very first images to bring to a sense of the great scale and enormity of the Antarctic landscape. Throughout the expedition, Hurley had taken photographs of the men working and also looking at the grandeur of the Antarctic landscape.

Such was Hurley’s and Shackleton’s desire to capture and preserve this visual evidence that when the Endurance sank, they took it upon themselves to rescue the glass plates of the iconic images and bring them to safety.

A Tale of Endurance

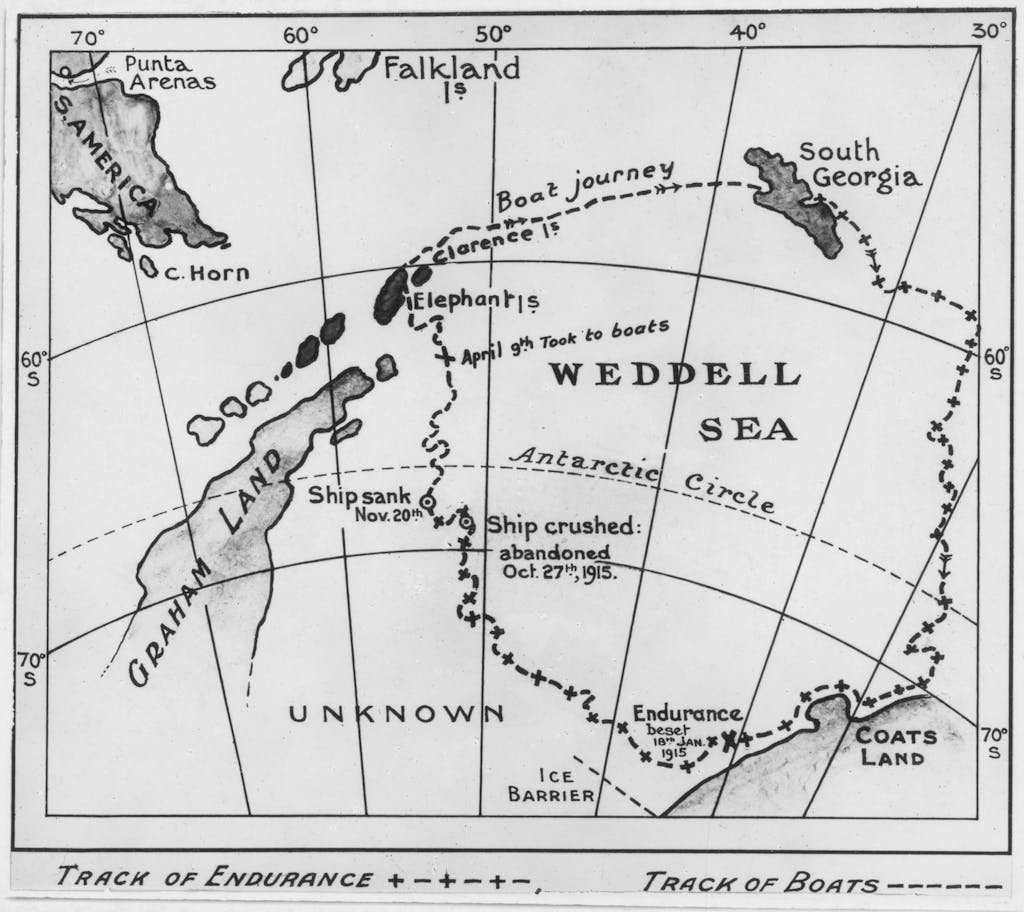

As an expedition with defined goals, the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition was a complete failure. Shackleton’s Weddell Sea party were unable to even land on the Antarctic continent as the Endurance was trapped and crushed by heavy pack-ice in the Weddell Sea. The Ross Sea party led by Aneas Mackintosh did manage to accomplish their task of laying supply depots but three men died and as Shackleton was unable to attempt the crossing of the continent, their efforts were in vain. Even so, the expedition has become famous for two extraordinary events, the 920 mile (1500 km) voyage of the James Caird from Elephant Island to South Georgia and Shackleton’s crossing of the rugged mountainous interior of the island to reach the whaling centre at Stromness Bay. Each was a remarkable achievement but together they are almost miraculous.

The Endurance expedition started well with Shackleton raising sufficient funds to purchase two ships, Endurance, a purpose built polar exploration ship and Aurora, previously used by Douglas Mawson during his Antarctic expedition. Endurance sailed from Plymouth in August 1914 and reached South Georgia on 5 November. The whalers based there informed Shackleton of very heavy ice in the Weddell Sea and advised him to delay sailing for a month.

It wasn’t until the 5 December that Endurance sailed from South Georgia and even with the delay she soon encountered heavy pack-ice. The Antarctic coast was sighted on 10 January and a possible landing place identified on 12 January. Shackleton wanted to land further south however, so they continued until on the 19 January the ship became stuck in the ice. Throughout the Antarctic winter Endurance became more and more firmly trapped until she finally sank.

After camping on the ice for several months Shackleton decided to try and reach Elephant Island. In three small boats, the James Caird, Dudley Docker and Stancomb Wills, 28 men began a life and death voyage. If they had missed Elephant Island they would have been swept into the South Atlantic where they would almost certainly have perished.

On 15 April 1916 the three small boats landed on Elephant Island. The chances of them being rescued from this remote spot were poor so after recuperating Shackleton and a small team sailed the James Caird, strengthened by the carpenter, McNish, and piloted by Frank Worsley, 920 miles to South Georgia, arriving on 10 May. They arrived to find an abundance of young albatrosses upon which they feasted liberally.

Although they had accomplished an incredible journey their troubles were not over. As William Mills wrote, South Georgia is a mountain range half-buried in the ocean. No one had penetrated more than a mile into its interior, and certainly no one had contemplated crossing from coast to coast as Shackleton and his colleagues must now do. The mountains that lay between Shackleton and the whaling station at Stromness rose to nearly 4000 feet (1200 meters) and the weary explorers had no specialist clothes or equipment. They fastened screws from the James Caird to their boots to act as crampons and on 19 May set off, traveling by moonlight. After traveling all night they heard the steam whistles from the whaling station at Stromness and by the afternoon of the 20 May they had reached safety. Shackleton wasted no time in arranging for the rescue of the men he had left on Elephant Island and then for the survivors of the Ross Sea party.

This article has been produced in collaboration with Silversea’s Corporate Business Partner, the Royal Geographical Society (with IBG), which enriches guests’ expeditions with over 500 years of geographical travel and discovery. Find out more here.