A Sewer Cover and a Skull Make One Rome Church a Must

This probably makes no sense to the casual observer. Inside one of Rome’s oldest churches, magnificent columns, murals and stonework might otherwise be the main tourist attractions. But here they gravitate to a sewer cover and a human skull. The Italian capital is laden with sublime architecture, but perhaps no other church in Rome has a pair of artifacts with such a mysterious history.

Bocca della Verità is a 3,000-pound marble sewer cover with a gaping mouth. Each day, hundreds of visitors poke their fingers into that opening, which is said to put them at risk from an ancient curse and to connect them with the blood sacrifices to a Greek demigod.

A few steps away, tourists stare at a human skull tied to the most romantic of days: It is said to belong to the legendary St. Valentine, whose remains are scattered across Europe.

If all of this sounds confusing, that’s because it is, until the tales of these two extraordinary, if puzzling objects are unraveled. Then they help underline the layer upon layer of intrigue built into the ancient cityscape of Rome.

It’s unassuming but don’t miss its surprises

Rome is, after all, a metropolis that began in startling fashion. U.S. cities typically had sedate beginnings, created by a British settler or Spanish explorer, but the lingering fable of Rome is that it was founded by twins Romulus and Remus, who were born to a war god and breastfed by a she-wolf. The actual founding of Rome is also shrouded in myths and fables, so the real origin story may never be known, but there remains evidence that in the 4th century BCE, the population of what would become Rome began to grow.

Nowadays, Rome overflows with glorious churches, stately mansions, commanding palaces and heavenly gardens. It’s so populated with sights that that tourists could easily overlook the endless, eerie artifacts, structures and stories behind the city’s glorious façade.

Case in point: The Basilica of Santa Maria in Cosmedin. This 1,500-year-old Catholic complex houses the sewer cover and the skull. From the street side of the basilica, passersby see an attractive, red-stone building decorated by arches and topped by a 112-foot Romanesque bell tower.

Many visitors do nothing more than admire its exterior. After all, Rome is replete with churches, so many that there is no official count, although estimates put the number at more than 600. Travelers tend to focus on the four, called major papal basilicas, most highly ranked by the Catholic church: St. Peter’s Basilica in Vatican City, the Basilica of St. Paul Outside the Walls, Basilica of St. Mary Major, and the Basilica of St. John Lateran.

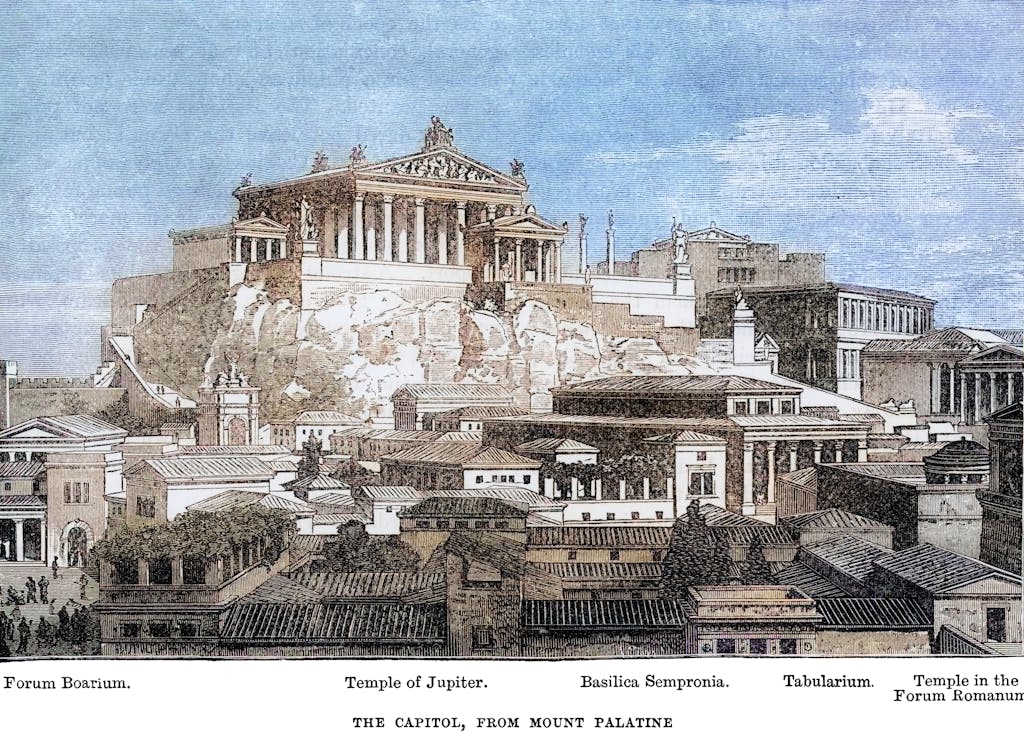

Santa Maria in Cosmedin is tucked alongside the Tiber River, separated from downtown Rome by the walled-off expanse of Palatine Hill and the Roman Forum (also pictured in photo at top of page). Although those sites are inundated with tourists, comparatively few wander around to the back to look in on Santa Maria in Cosmedin.

That’s not to say the basilica is insignificant or unimpressive. Pope Adrian I, who died on Christmas Day in 795 CE, valued it highly enough to enlarge Santa Maria in Cosmedin in 782. Three centuries later, Normans invaded Rome and badly damaged the building. It was rebuilt to its current, which now includes the entry porch that houses Bocca della Verità, also known as the Mouth of Truth.

This hefty circular mask, which sits atop a stone ledge, is 6 feet in diameter. It was carved from marble, supposedly to represent Oceanus, Greek god of the seas. He is depicted with flowing hair, a thick beard, long narrow nose, two round holes for his eyes and a large opening at his mouth.

Tourists line up to pose for photographs as they stick their digits into the mouth. It’s not disrespectful. They’re following an odd tradition that dates back more than 500 years to when Bocca della Verità was installed. It was thought to possess the power to detect lies. If you doubted the veracity of someone’s claim, you could dare that person to place their hand inside the Mouth of Truth.

If they were trustworthy, nothing happened. If they were lying, the mouth would slam shut and lop off their hand. Many Italian husbands forced their wives through this process to prove they were faithful.

The mythology of Bocca della Verità gets even grimier. It is widely thought to be more than 2,000 years old and connected to Cloaca Maxima, one of the first sewage systems ever built. (It’s just a few minutes from the basilica by the Tiber.) Visitors can spot an arched entrance to Cloaca Maxima, an enclosed stone network designed to channel waste away from the Roman Forum.

Bocca della Verità was eventually repurposed as an ornament at the Temple of Hercules Victor, a round building encircled by columns opposite the Basilica of Santa Maria in Cosmedin. At that temple, cult members were said to have used its mouth to drain the blood of beasts sacrificed to Hercules, the Roman version of the Greek hero Heracles.

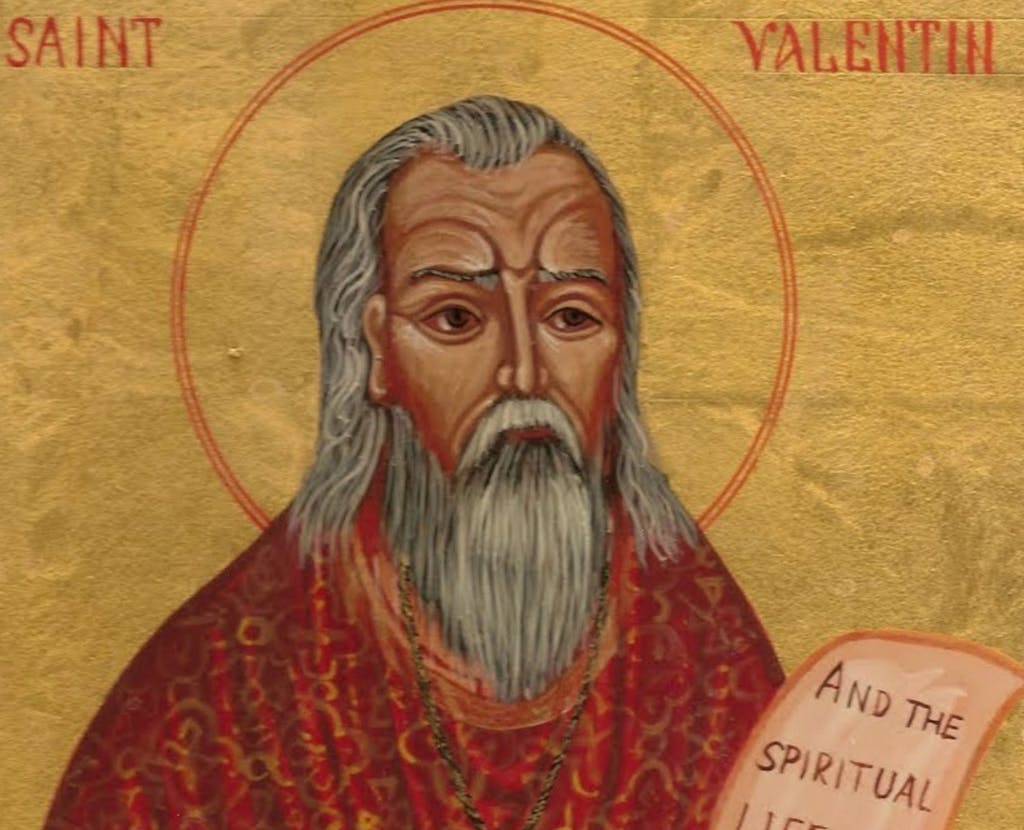

St. Valentine and his crown of flowers

You can find monuments to Hercules throughout Italy and Greece. Spread even more widely across Europe are what are claimed to be physical remains of St Valentine. A dozen churches in Italy, Poland, Malta, Spain, England, Scotland, Ireland, Greece and the Czech Republic, each display what they claim are parts of his body.

St. Valentine was a Christian martyr, executed more than 1,700 years ago, supposedly for secretly marrying couples so the husband wouldn’t have to join the Roman military. Valentine was celebrated each Feb. 14, which changed from a religious feast to Valentine’s Day, the world’s biggest annual festival of love.

St. Valentine was so popular, even in ancient times, that churches could attract visitors and thus income by acquiring and showcasing his relics. Pilgrims commonly traveled long distances to see the remains of their favorite saints, and that created lucrative opportunities for relic traders. These men went from church to church trying to sell the skulls, bones, fingernails, even hair of holy men. They had no proof, only their word.

That’s why so many churches still exhibit apparent pieces of St Valentine. His shoulder blade is displayed in Prague, Czech Republic, his desiccated heart in Dublin, Ireland, his skeleton in Glasgow, Scotland, his bone fragments in Malta. We may never know which of them, if any, is authentic.

For now, they remain attractions that transfix visitors to Catholic complexes like this Rome basilica. It has put great effort into displaying the macabre relic as beautifully as possible. Inside its large, dimly lit prayer hall is a gilded, glass reliquary box. Tourists peer inside and see a skull, said to be St. Valentine, wearing a flower crown.

Then they go outside to poke the Mouth of Truth before moving on through Rome and marveling at its array of churches, many far more spectacular than the Basilica of Santa Maria in Cosmedin. Still, none matches the intrigue of its peculiar pair of artifacts.